The Generalized Interpersonal Theory

Completion of the Human Genome Project signaled the beginning of a new era in understanding the contributions of genes to human behavior, yet this understanding will never eliminate the importance of environments, for genes invariably work in combination with environments. Interpersonal theorists' great contributions to human enviromics (Anthony, 2001; Anthony, Eaton, & Henderson, 1995; Eaton, 2001; Eaton & Harrison, 1998) are a structural model of the interpersonal domain and an understanding of dyadic interactions.

The Structural Model: Individual Differences and Psychopathology

In recent years, a consensus has been building on the structure of personality traits. It appears that five broad dimensions--extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience--are necessary to describe personality across many cultures (e.g., Digman, 1990; Goldberg, 1993; McCrae & Costa, 1997; Wiggins, 1996). In addition, recent studies have converged on a common structure of psychological disorders. It appears that two broad dimensions, internalization (feeling bad) and externalization (making others feel bad), are necessary to describe psychopathology in many large-scale epidemiological and treatment-seeking samples in multiple cultures (e.g., Acton, 2003; Acton, Kunz, Wilson, & Hall, 2005; Bienvenu et al., 2004; Burt, Krueger, McGue, & Iacono, 2001, 2003; Cooper, Wood, Orcutt, & Albino, 2003; Hicks, Krueger, Iacono, McGue, & Patrick, 2004; Hudson et al., 2003; Hudson & Pope, 1990; Iacono, Carlson, Malone, & McGue, 2002; Kendler, Neale, Kessler, Heath, & Eaves, 1992a, 1992b; Kendler, Prescott, Myers, & Neale, 2003; Kendler et al., 1995; Krueger, 1999; Krueger, Caspi, Moffitt, & Silva, 1998; Krueger, Chentsova-Dutton, Markon, Goldberg, & Ormel, 2003; Krueger et al., 2002; Krueger & Finger, 2001; Lahey et al., 2004; Nestadt et al., 2001; Vollebergh et al., 2001). In order to provide a framework for understanding these robust findings, the GIPT draws upon several theoretical traditions. Chief among these is the interpersonal theory of personality (e.g., Acton & Revelle, 2002, 2004; Carson, 1969; Kiesler, 1983; Leary, 1957; Wiggins, 1979). The GIPT expands and reformulates key elements of classical interpersonal theory while preserving other important elements.

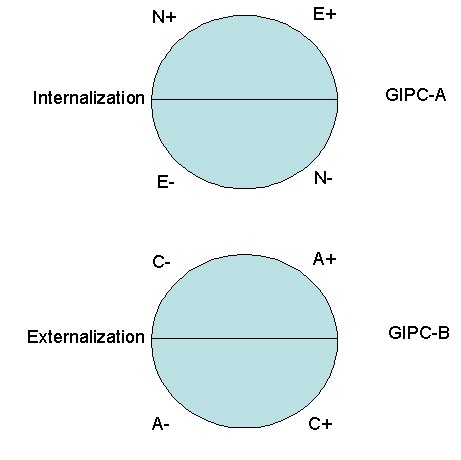

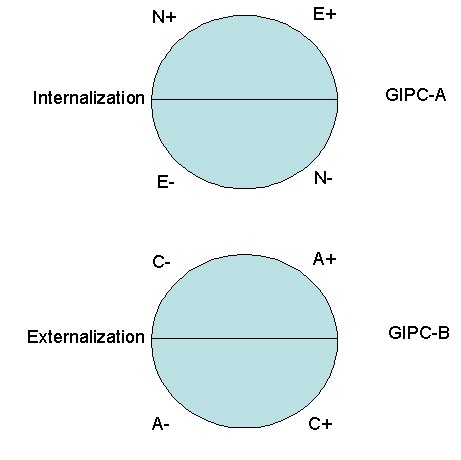

For example, the GIPT expands the definition of what is considered interpersonal. Formerly, only the traits of extraversion and agreeableness were included in the interpersonal circle (McCrae & Costa, 1989). The GIPT includes a structural model with an extraversion-neuroticism circle of temperament (the Generalized Interpersonal Circumplex A, GIPC-A) and an agreeableness-conscientiousness circle of character (the Generalized Interpersonal Circumplex B, GIPC-B) (Figure 1) (cf. Hofstee, de Raad, & Goldberg, 1992). This structural model comprises a construct map (Wilson, 2005) for the interpersonal domain. Because openness is more cognitive in nature and does not appear to have direct affective consequences (Watson, 2000), because it is the least consistently found cross-culturally of the Big Five (De Raad, Perugini, Hrebickova, & Szarota, 1998; Saucier & Goldberg, 2001), and because it appears to have limited relevance to psychopathology (O'Connor & Dyce, 1998; Widiger, 1993), it is not included in the structural model.

The GIPT proposes that common mental disorders can be conceptualized as extreme manifestations of normal personality dimensions (e.g., Acton, 1998; Acton & Zodda, 2005). Because of the influence of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), psychological disorders are usually conceptualized as categories (but see, e.g., Mirowsky & Ross, 1989, 2002). Nevertheless, dimensional models of personality disorders have increasingly inspired considerable enthusiasm among psychopathology researchers (e.g., Costa & Widiger, 2002; O'Connor & Dyce, 1998; Widiger, 1993; Widiger & Costa, 1994). Only recently, however, have dimensional models of syndromal (Axis I) disorders such as major depression and drug dependence been proposed and tested empirically. Using confirmatory factor analysis and item response theory, researchers have shown that unipolar mood and anxiety disorders form a common dimension of internalization (e.g., Acton et al., 2005; Bienvenu et al., 2004; Hudson et al., 2003; Hudson & Pope, 1990; Kendler et al., 1992a, 1992b; Kendler et al., 1995; Kendler et al., 2003; Krueger, 1999; Krueger et al., 1998; Krueger et al., 2003; Krueger & Finger, 2001; Lahey et al., 2004; Nestadt et al., 2001; Vollebergh et al., 2001) and that antisocial behavior, substance use disorders, and impulsivity/disinhibition form a common dimension of externalization (e.g., Acton, 2003; Burt et al., 2001, 2003; Cooper et al., 2003; Hicks et al., 2004; Iacono et al., 2002; Kendler et al., 2003; Krueger, 1999; Krueger et al., 1998; Krueger et al., 2002; Krueger et al., 2003; Lahey et al., 2004; Vollebergh et al., 2001) (cf. Table 1).

Research on internalizing and externalizing disorders is important (a) because it shows what the most important dimensions of psychopathology might be, and (b) because it is consistent across many diverse large-scale data sets. What it does not show, however, is that these disorders are in fact dimensional--because factor analysis and item response theory will always find dimensions, and thus it is trivially true that internalization and externalization are descriptive dimensions. To examine the next step in this research program requires a conceptual and psychometric framework in which both dimension-likeness and category-likeness are possible and can be tested empirically. The dimension/category framework (Dimcat) (De Boeck, Wilson, & Acton, 2005) is such a framework. Dimcat specifies a method by which manifest categories, such as a diagnosis of major depression versus its complement (another diagnosis or the absence of a diagnosis), can be shown to be dimensional or categorical with respect to an underlying descriptive dimension, such as internalization.

The first distinction in Dimcat is among levels of within-category homogeneity on the indicators as measured by Cronbach's alpha. A population that was maximally heterogeneous on the risk-factors for a disorder would warrant a universal preventive intervention, a population that was moderately homogeneous would warrant a selective preventive intervention, a population that was highly homogeneous would warrant an indicated preventive intervention, and a population that was maximally homogeneous would warrant an evidence-based treatment (cf. Mrazek & Haggerty, 1994).

The second distinction in Dimcat is between between-category qualitative versus quantitative differences on the indicators as measured by differential item functioning (DIF). It has been suggested that the boundary demarcating mental disorder is fuzzy (e.g., Lilienfeld & Marino, 1995) and expanding (e.g., Blashfield & Fuller, 1996). Although part of the discussion has centered on professional and economic issues, the basic question--is mental illness qualitatively distinct from mental health?--is both empirical and tractable using Dimcat, assuming merely that fallible indicators of this distinction can be identified, along with groups representing the mentally ill and healthy.

A longitudinal perspective on this question concerns premorbid risk-factors for a given disorder: Is there a qualitatively distinct type of individual who is particularly at risk? If so, then preventive interventions should focus on all and only individuals of that type. Here, as elsewhere, the categories chosen are everything. In a cohort study of adolescents in the community, for example, an eventual DSM-IV diagnosis of nicotine dependence may differ on the risk-factors (e.g., impulsivity items) at baseline only quantitatively (e.g., Acton, 2003), but more socially potent categories (e.g., peer group, social roles) at baseline may indeed be qualitatively distinct. Later, a diagnosis may become qualitatively distinct as it begins to exert a social influence all its own (e.g., Link, Cullen, Struening, Shrout, & Dohrenwend, 1989; Scheff, 1999) in the manner of a self-fulfilling prophesy, wherein the diagnostic label becomes a social role that evokes certain types of responses from others and may even be used for manipulation (Buss, 1987). Goffman (1961, 1963) was one of the first to describe the process of association between deviance and stigma, which Castro and Farmer (2005) included under the rubric structural violence. Hypotheses concerning the processes of forming qualitatively distinct categories could be tested through a conception-to-death cohort study (Eaton, 2002).

The Dynamic Model: Personality Processes and Psychotherapy

The strongest aspect of classical interpersonal theory is its specification of patterns of dyadic interactions. An unpublished meta-analysis indicated that state-level specifications of dyadic interactions as sequences of behaviors had large effect sizes, much more so than trait-level specifications of dyadic interactions as global or summative ratings. According to the most common model for interpersonal complementarity (e.g., Carson, 1969; Kiesler, 1983; Markey, Funder, & Ozer, 2003) when understood in relation to the five-factor model (McCrae & Costa, 1989), agreeable behaviors probabilistically cause extraverted behaviors in others, and vice versa, whereas disagreeable behaviors probabilistically cause introverted behaviors in others, and vice versa.

In the dynamic model of the GIPT, the classical interpersonal principle of complementarity is preserved, expanded, and reformulated. In Figure 1, complementary traits are located at similar positions on each circle. For example, the complement of low conscientiousness is high neuroticism--that is, non-conscientious behavior (e.g., not completing one's duties in a timely manner) causes others to feel distress. In contrast to complementarity, anticomplementarity, or the antidote, can be defined as the opposite of the complement. An anticomplementary response is the treatment for an unwanted trait. For example, high conscientiousness is the antidote for high neuroticism. To help reduce the expression of the unwanted trait of high neuroticism, people in the social environment--friends, family, even strangers--would need to act in a highly conscientious manner, being very careful of their words and actions, walking on eggshells, so to speak.

Lewin's (1936) classic formulation assumed that Behavior = f(Person, Environment); the present model, by contrast, is explicitly probabilistic: Pr(Behavior) = f(Person, Environment). Rasch (1960), best known for his one-parameter logistic model, formulated a family of Rasch models such that Pr(X = 1) = f(q + b) (see also Mellenbergh, 1994). In this model, X = 1 can be understood as a target individual's exhibiting a particular state (i.e., behavior or affect), q can be understood as the target's own corresponding trait, and b can be understood as a partner's complementary state.

This model can be used to test all of the competing formulations of interpersonal complementarity (e.g., Carson, 1969; Myllyniemi, 1997; Strong et al., 1988; Wiggins, 1979), including Acton and Zodda's (2005) generalized interpersonal principle of complementarity. First, a pool of unidimensional items measuring the states of a generalized partner must be calibrated. Second, the target individual's level on the complementary trait must be measured. Third, the target and partner must be observed over time in an experience-sampling study, cohort study, or clinical trial. Fourth, the correlations among the target's actually exhibited states over time can be tested for circumplex structure (e.g., Acton & Revelle, 2002, 2004). In epidemiolgic terms, complementarity is a model for incidence or initiating a new behavior, and circumplex structure is a model interrelating the prevalences of different behaviors over a given time (Eaton, 1975; see also Moskowitz & Zuroff, 2004). In addition to the circumplex, a competing model for the structure of behavior is a hierarchial model (Markon, Krueger, & Watson, 2005). The relative fit of these structures can be tested using randomization tests of hypothesized order relations (Hubert & Arabie, 1987; see also Tracey & Rounds, 1993), but the principle of complementarity as formulated here does not depend on one structure fitting better than the other.

This model can be expanded to include anticomplementary social roles, in which the target's exhibited state departs from complementarity owing to rigidity (including role disputes, role transitions, and therapeutic noncompliance with a patient's problematic states) (e.g., Eagly & Karau, 2002; Weissman, Markowitz, & Klerman, 2000) or residual deviance for which no term exists (including interpersonal skills deficits and bizarre noncomformity) (e.g., Cannon, 1942; Estroff, Lachicotte, Illingworth, & Johnston, 1991; Link, Cullen, Struening, Shrout, & Dohrenwend, 1989; Scheff, 1999; Weissman et al., 2000). Rigidity can be described as being firm and unyielding in the face of the interpersonal situation, whereas residual deviance can be described as acting out a social role that is utterly out of context. Rigidity can be modeled as uniform DIF: Pr(X = 1) = f(q + b + z), where z is the effect of the anticomplementary role. Residual deviance can be modeled as nonuniform DIF: Pr(X = 1) = f(q + b + z + z*q) (cf. Mellenbergh, 1994).

This model can be expanded still further by regressing q and b onto their causes (De Boeck & Wilson, 2004; Rijmen, Tuerlinckx, De Boeck, & Kuppens, 2003). For example, interdependence theory models the causes of a partner's state as a function of the partner's outcome expectancies relative to the target's, based on which Kelley et al. (2003) constructed an entire atlas of interpersonal situations. Similarly, a target's personality trait is likely caused by a number of fixed (genome and intrafamilial environment) and latent (peer group) effects (e.g., Harris, 1995).

The dynamic model provides a framework for understanding how psychopathology can be relieved. Warmth and empathy plus consistency and setting limits may be among the nonspecific elements--reflecting agreeable and conscientious behavior, respectively--that provide new interpersonal experiences that Linehan (1993) identified as the dialectic between acceptance and change. These new interpersonal experiences may be chief ingredients that make most forms of psychotherapy substantially and about equally effective (e.g., Frank & Frank, 1991; Strupp & Hadley, 1979; Wampold, 2001; Wampold et al., 1997). In some cases, relationship-focused psychotherapy, for example, precipitates sudden relief of depressive symptoms (Tang, Luborsky, & Andrusyna, 2002). One form of psychotherapy with demonstrated efficacy for internalizing disorders--namely, interpersonal psychotherapy--was developed as a manualized form of nonspecific elements (Weissman et al., 2000). The efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy proved so robust that it relieved depressive symptoms and improved functioning even when delivered after 2-weeks' training by indiginous, nonprofessional residents of rural Uganda (Bolton et al., 2003). Indeed, interventions that improve interpersonal relationships may immunize the population against onset of mental disorders (Mrazek & Haggerty, 1994) and physical disorders such as HIV (Castro & Farmer, 2005; Peace Corps, 2001).

The dynamic model provides a framework for understanding how psychopathology can be relieved. Warmth and empathy plus consistency and setting limits may be among the nonspecific elements--reflecting agreeable and conscientious behavior, respectively--that provide new interpersonal experiences that Linehan (1993) identified as the dialectic between acceptance and change. These new interpersonal experiences may be chief ingredients that make most forms of psychotherapy substantially and about equally effective (e.g., Frank & Frank, 1991; Strupp & Hadley, 1979; Wampold, 2001; Wampold et al., 1997). In some cases, relationship-focused psychotherapy, for example, precipitates sudden relief of depressive symptoms (Tang, Luborsky, & Andrusyna, 2002). One form of psychotherapy with demonstrated efficacy for internalizing disorders--namely, interpersonal psychotherapy--was developed as a manualized form of nonspecific elements (Weissman et al., 2000). The efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy proved so robust that it relieved depressive symptoms and improved functioning even when delivered after 2-weeks' training by indiginous, nonprofessional residents of rural Uganda (Bolton et al., 2003). Indeed, interventions that improve interpersonal relationships may immunize the population against onset of mental disorders (cf. Mrazek & Haggerty, 1994).

The dynamic model also provides a framework for understanding how psychopathology is perpetuated. Depression and anxiety (internalizing disorders) tend to elicit rejection (externalizing behavior) (e.g., Coyne, 1976a, 1976b; Joiner & Coyne, 1999; Nolan, Flynn, & Garber, 2003; Pineles, Mineka, & Nolan, 2004), and maternal depression predicts childhood externalizing behaviors (Akse, Hale, Engles, Raaijmakers, & Meeus, 2004; Kim-Cohen, Moffitt, Taylor, Pawlby, & Caspi, 2005; Nelson, Hammen, Brennan, & Ullman, 2003). Moreover, expressed emotion (criticalness, hostility, or emotional overinvolvement--all externalizing behaviors) in family or friends is associated with relapse in mood disorders and eating disorders (internalizing disorders) (e.g., Butzlaff & Hooley, 1998; Hooley, 1986; Hooley, Orley, & Teasdale, 1986; Hooley & Teasdale, 1989) and with social phobia (an internalizing disorder) (Lieb et al., 2000). These lines of research are consistent with the contention that internalization is the complement of externalization.

Overall, the GIPT generalizes classical interpersonal theory by including two additional traits from the Big Five personality dimensions, and it provides a method for testing whether common mental disorders are extreme manifestations of these personality dimensions. It also provides a framework for predicting affect and behavior in interpersonal interactions based on the same predisposing personality dimensions, and this framework explains why psychopathology persists and how it can be relieved.

References

Acton, G. S. (1998). Classification of psychopathology: The nature of language. The Journal of Mind and Behavior, 19, 243-256.

Acton, G. S. (2003). Measurement of impulsivity in a hierarchical model of personality traits: Implications for substance use. Substance Use & Misuse, 38, 67-83.

Acton, G. S., Kunz, J. D., Wilson, M., & Hall, S. M. (2005). The construct of internalization: Conceptualization, measurement, and prediction of smoking treatment outcome. Psychological Medicine, 35, 395-408.

Acton, G. S., & Revelle, W. (2002). Interpersonal personality measures show circumplex structure based on new psychometric criteria. Journal of Personality Assessment, 79, 456-481.

Acton, G. S., & Revelle, W. (2004). Evaluation of ten psychometric criteria for circumplex structure. Methods of Psychological Research, 9, 1-27.

Acton, G. S., & Zodda, J. J. (2005). Classification of psychopathology: Goals and methods in an empirical approach. Theory & Psychology, 15, 373-399.

Adler, A. (1939). Social interest. New York: Putnam.

Akse, J., Hale, W. W., III, Engles, R. C. M. E., Raaijmakers, Q. A. W., & Meeus, W. H. J. (2004). Personality, perceived parental rejection and problem behavior in adolescence. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 39, 980-988.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Anthony, J. C. (2001). The promise of psychiatric enviromics. British Journal of Psychiatry, 178, S8-S11.

Anthony, J. C., Eaton, W. W., & Henderson, A. S. (1995). Looking into the future in psychiatric epidemiology. Epidemiologic Reviews, 17, 240-242.

Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 226-244.

Beck, A. T. (1983). Cognitive therapy of depression: New perspectives. In P. J. Clayton & J. E. Barrett (Eds.), Treatment of depression: Old controversies and new approaches (pp. 265-290). New York: Raven.

Bem, S. L. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42, 155-162.

Bienvenu, O. J., Samuels, J. F., Costa, P. T., Reti, I. M., Eaton, W. W., & Nestadt, G. (2004). Anxiety and depressive disorders and the five-factor model of personality: A higher- and lower-order personality trait investigation in a community sample. Depression and Anxiety, 20, 92-97.

Blashfield, R. K., & Fuller, A. K. (1996). Predicting the DSM-V. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 186, 244-246.

Blatt, S. J., D'Afflitti, J. P., & Quinlan, D. M. (1976). Experiences of depression in normal young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 85, 383-389.

Bolton, P., Bass, J., Neugebauer, R., Verdeli, H., Clougherty, K. F., Wickramaratne, P., Speelman, L., Ndogoni, L., & Weissman, M. (2003). Group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in rural Uganda: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association, 289, 3117-3124.

Burt, S. A., Krueger, R. F., McGue, M., & Iacono, W. G. (2001). Sources of covariation among attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder: The importance of shared environment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 516-525.

Burt, S. A., Krueger, R. F., McGue, M., & Iacono, W. (2003). Parent-child conflict and the comorbidity among childhood externalizing disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 505-513.

Buss, D. M. (1987). Selection, evocation, and manipulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 1214-1221.

Buss, D. M. (1992). Manipulation in close relationships: Five personality factors in interactional context. Journal of Personality, 60, 477-499.

Butzlaff, R. L., & Hooley, J. M. (1998). Expressed emotion and psychiatric relapse: A meta-analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry, 55, 547-552.

Cannon, W. B. (1942). "Voodoo" death. American Anthropologist, 44, 169-181.

Carson, R. C. (1969). Interaction concepts of personality. Chicago: Aldine.

Caspi, A., Elder, G. H., Jr., & Bem, D. J. (1987). Moving against the world: Life-course patterns of explosive children. Developmental Psychology, 23, 308-313.

Caspi, A., Elder, G. H., Jr., & Bem, D. J. (1988). Moving away from the world: Life-course patterns of shy children. Developmental Psychology, 24, 824-831.

Castro, A., & Farmer, P. (2005). Understanding and addressing AIDS-related stigma: From anthropological theory to clinical practice in Haiti. American Journal of Public Health, 95, 53-59.

Cloninger, C. R. (1987). A systematic method for description and classification of personality variants: A proposal. Archives of General Psychiatry, 44, 573-588.

Cooper, M. L., Wood, P. K., Orcutt, H. K., & Albino, A. (2003). Personality and the predisposition to engage in risky or problem behaviors during adolescence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 390-410.

Costa, P. T., Jr., & Widiger, T. A. (Eds., 2002). Personality disorders and the five-factor model of personality (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Coyne, J. C. (1976a). Depression and the response of others. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 85, 186-193.

Coyne, J. C. (1976b). Toward an interactional description of depression. Psychiatry, 39, 28-40.

Darwin, C. (1872). The expression of emotion in men and animals. London: John Murray.

De Boeck, P., & Wilson, M. (Eds., 2004). Explanatory item response models: A generalized linear and nonlinear approach. New York: Springer.

De Boeck, P., Wilson, M., & Acton, G. S. (2005). A conceptual and psychometric framework for distinguishing categories and dimensions. Psychological Review, 112, 129-158.

De Raad, B., Perugini, M., Hrebickova, M., & Szarota, P. (1998). Lingua franca of personality: Taxonomies and structures based on the psycholexical approach. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 29, 212-232.

Durkheim, E. (1951). Suicide: A study in sociology (J. A. Spaulding & G. Simpson, Trans.). Glencoe, IL: Free Press. (Original work published 1897)

Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109, 573-598.

Eaton, W. W. (1975). Causal models for the study of prevalence. Social Forces, 54, 417-426.

Eaton, W. W. (2001). The sociology of mental disorders (3rd ed.). New York: Praeger.

Eaton, W. W., & Harrison, G. (1998). Epidemiology and social aspects of the human envirome. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 11, 165-168.

Elliot, A. J., & Thrash, T. M. (2002). Approach-avoidance motivation in personality: Approach and avoidance temperaments and goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 804-818.

Erickson, E. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton.

Estroff, S. E., Lachicotte, W. S., Illingworth, L. C., & Johnston, A. (1991). Everybody's got a little mental illness: Accounts of illness and self among people with severe, persistent mental illnesses. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 5, 331-369.

Eysenck, H. J. (1992). The definition and measurement of psychoticism. Personality and Individual Differences, 13, 757-785.

Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, M. W. (1985). Personality and individual differences: A natural science approach. New York: Plenum.

Frank, J. D., & Frank, J. B. (1991). Persuasion and healing: A comparative study of psychotherapy (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Frankl, V. E. (1963). Man's search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy (I Lasch, Trans.). New York: Washington Square Press. (Original work published 1946)

Freud, S. (1930). Civilization and its discontents. New York: Norton.

Fromm, E. (1941). Escape from freedom. New York: Avon Books.

Goffman, E. (1961). Asylums: Essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates. Garden City, NY: Anchor.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Garden City, NY: Anchor.

Goldberg, L. R. (1993). The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American Psychologist, 48, 26-34.

Gray, J. A. (1982). Précis of The neuropsychology of anxiety: An enquiry into the functions of the septo-hippocampal system. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 5, 469-534.

Harris, J. R. (1995). Where is the child's environment? A group socialization theory of development. Psychological Review, 102, 458-489.

Hicks, B. M., Krueger, R. F., Iacono, W. G., McGue, M., & Patrick, C. J. (2004). Family transmission and heritability of externalizing disorders: A twin-family study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61, 922-928.

Hofstee, W. K. B., De Raad, B., & Goldberg, L. R. (1992). Integration of the Big Five and circumplex approaches to trait structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 146-163.

Hogan, R. (1982). A socioanalytic theory of personality. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 30, 55-89.

Hooley, J. M. (1986). Expressed emotion and depression: Interactions between patients and high- versus low-expressed emotion spouses. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 95, 237-246.

Hooley, J. M., Orley, J., & Teasdale, J. D. (1986). Levels of expressed emotion and relapse in depressed patients. British Journal of Psychiatry, 148, 642-647.

Hooley, J. M., & Teasdale, J. D. (1989). Predictors of relapse in unipolar depressives: Expressed emotion, marital distress, and perceived criticism. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 98, 229-235.

Horney, K. (1945). Our inner conflicts. New York: Norton.

Hubert, L., & Arabie, P. (1987). Evaluating order hypotheses within proximity matrices. Psychological Bulletin, 102, 172-178.

Hudson, J. I., Mangweth, B., Pope, H. G., Jr., De Col, C., Hausmann, A., Gutweniger, S., Laird, N. M., Biebl, W., & Tsuang, M. T. (2003). Family study of affective spectrum disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 170-177.

Hudson, J. I., & Pope, H. G., Jr. (1990). Affective spectrum disorder: Does antidepressant response identify a family of disorders with a common pathophysiology? American Journal of Psychiatry, 147, 552-564.

Iacono, W. G., Carlson, S. R., Malone, S. M., & McGue, M. (2002). P3 event-related potential amplitude and the risk for disinhibitory disorders in adolescent boys. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59, 750-757.

Joiner, T., & Coyne, J. C. (Eds., 1999). The interactional nature of depression: Advances in interpersonal approaches. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Kelley, H. H., Holmes, J. G., Kerr, N. L., Reis, H. T., Rusbult, C. E., & Van Lange, P. A. M. (2003). An atlas of interpersonal situations. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kendler, K. S., Neale, M. C., Kessler, R. C., Heath, A. C., & Eaves, L. J. (1992). Major depression and generalized anxiety disorder: Same genes, (partly) different environments? Archives of General Psychiatry, 49, 716-722.

Kendler, K. S., Prescott, C. A., Myers, J., & Neale, M. C. (2003). The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 929-937.

Kiesler, D. J. (1983). The 1982 interpersonal circle: A taxonomy for complementarity in human transactions. Psychological Review, 90, 185-214.

Kim-Cohen, J., Moffitt, T. E., Taylor, A., Pawlby, S. J., & Caspi, A. (2005). Maternal depression and children's antisocial behavior: Nature and nurture effects. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 173-181.

Krueger, R. F. (1999). The structure of common mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56, 921-926.

Krueger, R. F., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., & Silva, P. E. (1998). The structure and stability of common mental disorders (DSM-III-R): A longitudinal-epidemiological study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107, 216-227.

Krueger, R. F., Chentsova-Dutton, Y. E., Markon, K. E., Goldberg, D., & Ormel, J. (2003). A cross-cultural study of the structure of comorbidity among common psychopathological syndromes in the general health care setting. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 437-447.

Krueger, R. F., & Finger, M. S. (2001). Using item response theory to understand comorbidity among anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Psychological Assessment, 13, 140-151.

Krueger, R. F., Hicks, B. M., Patrick, C. J., Carlson, S. R., Iacono, W. G., & McGue, M. (2002). Etiologic connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior, and personality: Modeling the externalizing spectrum. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111, 411-424.

Lahey, B. B., Applegate, B., Waldman, I. D., Loft, J. D., Hankin, B. L., & Rick, J. (2004). The structure of child and adolescent psychopathology: Generating new hypotheses. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113, 358-385.

Leary, T. (1957). Interpersonal diagnosis of personality. New York: Ronald.

Lewin, K. (1936). Principles of topological psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Lieb, R., Wittchen, H. U., Höfler, M., Fuetsch, M., Stein, M. B., & Merikangas, K. R. (2000). Parental psychopathology, parenting styles, and the risk of social phobia in offspring. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57, 859-866.

Lilienfeld, S. O., & Marino, L. (1995). Mental disorder as a Roschian concept: A critique of Wakefield's harmful dysfunction analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104, 411-420.

Linehan, M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford.

Link, B. G., Cullen, F. T., Struening, E., Shrout, P. E., & Dohrenwend, B. P. (1989). A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: An empirical assessment. American Sociological Review, 54, 400-423.

Markey, P. M., Funder, D. C., & Ozer, D. J. (2003). Complementarity of interpersonal behaviors in dyadic interactions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 1082-1090.

Markon, K. E., Krueger, R. F., & Watson, D. (2005). Delineating the structure of normal and abnormal personality: An integrative hierarchical approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 139-157.

Maslow, A. H. (1962). Toward a psychology of being. Oxford, England: Van Nostrand.

McAdams, D. P. (1985). Power, intimacy, and the life story: Psychological inquiries into identity. Homewood, IL: Dow-Jones-Irwin.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1989). The structure of interpersonal traits: Wiggins's circumplex and the five-factor model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 586-595.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1997). Personality trait structure as a human universal. American Psychologist, 52, 509-516.

Mellenbergh, G. J. (1994). Generalized linear item response theory. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 300-307.

Mirowsky, J., & Ross, C. E. (1989). Psychiatric diagnosis as reified measurement. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 30, 11-25.

Mirowsky, J., & Ross, C. E. (2002). Measurement for a human science. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43, 152-170.

Moskowitz, D. S., & Zuroff, D. C. (2004). Flux, pulse, and spin: Dynamic additions to the personality lexicon. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 880-893.

Mrazek, P. J., & Haggerty, R. J. (Eds., 1994). Reducing risks for mental disorders: Frontiers for preventive intervention research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Myllyniemi, R. (1997). The interpersonal circle and emotional undercurrents of human sociability. In R. Plutchik & H. R. Conte (Eds.), Circumplex models of personality and emotions (pp. 271-298). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Nelson, D. R., Hammen, C., Brennan, P. A., & Ullman, J. B. (2003). The impact of maternal depression on adolescent adjustment: The role of expressed emotion. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 935-944.

Nestadt, G., Samuels, J., Riddle, M. A., Liang, K. Y., Bienvenu, O. J., Hoehn-Saric, R., Grados, M., & Cullen, B. (2001). The relationship between obsessive-compulsive disorder and anxiety and affective disorders: Results from the Johns Hopkins OCD Family Study. Psychological Medicine, 31, 481-487.

Nolan, S. A., Flynn, C., & Garber, J. (2003). Prospective relations between rejection and depression in young adolescents. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 745-755.

O'Connor, B. P., & Dyce, J. A. (1998). A test of models of personality disorder configuration. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107, 3-16.

Peace Corps (2001). Life skills manual. Washington, DC: Center for Field Assistance and Applied Research, Information Collection and Exchange. (Publication No. M0063)

Pineles, S. L., Mineka, S., & Nolan, S. A. (2004). Interpersonal appraisals of emotionally distressed persons by anxious and dysphoric individuals. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 18, 779-797.

Rank, O. (1945). Will therapy and truth and reality. New York: Knopf.

Rasch, G. (1960). Probabilistic models for some intelligence and attainment tests. Copenhagen, Denmark: Danish Institute for Educational Research.

Rijmen, F., Tuerlinckx, F., De Boeck, P., & Kuppens, P. (2003). A nonlinear mixed model framework for item response theory. Psychogical Methods, 8, 185-205.

Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person. Boston: Houghton Miflin.

Saucier, G., & Goldberg, L. R. (2001). Lexical studies of indigenous personality factors: Premises, products, and prospects. Journal of Personality, 69, 847-880.

Scheff, T. J. (1990). Microsociology: Discourse, emotion, and social structure. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Scheff, T. J. (1999). Being mentally ill: A sociological theory (3rd ed.). Chicago: Aldine.

Skinner, B. F. (1971). Beyond freedom and dignity. New York: Knopf.

Spielberger, C. D., Krasner, S. S., & Solomon, E. P. (1988). The experience, expression, and control of anger. In M. P. Janisse (Ed.), Health psychology: Individual differences and stress (pp. 89-108). New York: Springer.

Strong, S. R., Hills, H. I., Kilmartin, C. T., DeVries, H., Lanier, K., Nelson, B. N., Strickland, D., & Myer, C. W., III (1988). The dynamic relations among interpersonal behaviors: A test of complementarity and anticomplementarity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 798-810.

Strupp, H. H., & Hadley, S. W. (1979). Specific versus nonspecific factors in psychotherapy. Archives of General Psychiatry, 36, 1125-1136.

Sullivan, H. S. (1953). The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. New York: Norton.

Tang, T. Z., Luborsky, L., & Andrusyna, T. (2002). Sudden gains in recovering from depression: Are they also found in psychotherapies other than cognitive-behavioral therapy? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 444-447.

Tracey, T. J., & Rounds, J. (1993). Evaluating Holland's and Gati's vocational-interest models: A structural meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 229-246.

Vollebergh, W. A. M., Iedema, J., Bijl, R. V., de Graaf, R., Smit, F., & Ormel, J. (2001). The structure and stability of common mental disorders: The NEMESIS study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58, 597-603.

Wampold, B. E. (2001). The great psychotherapy debate: Models, methods, and findings. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Wampold, B. E., Mondin, G. W., Moody, M., Stich, F., Benson, K., & Ahn, H. N. (1997). A meta-analysis of outcome studies comparing bona fide psychotherapies: Empirically, "all must have prizes." Psychological Bulletin, 122, 203-215.

Watson, D. (2000). Mood and temperament. New York: Guilford.

Watson, D., Wiese, D., Vaidya, J., & Tellegen, A. (1999). The two general activation systems of affect: Structural findings, evolutionary considerations, and psychobiological evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 820-838.

Weissman, M. M., Markowitz, J. C., & Klerman, G. L. (2000). Comprehensive guide to interpersonal psychotherapy. New York: Basic.

Widiger, T. A. (1993). The DSM-III-R categorical personality disorder diagnoses: A critique and an alternative. Psychological Inquiry, 4, 75-90.

Widiger, T. A., & Costa, P. T. (1994). Personality and personality disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103, 78-91.

Wiggins, J. S. (1979). A psychological taxonomy of trait-descriptive terms: The interpersonal domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 395-412.

Wiggins, J. S. (1991). Agency and communion as conceptual coordinates for the understanding and measurement of interpersonal behavior. In W. M. Grove & D. Cicchetti (Eds.), Thinking clearly about psychology: Essays in honor of Paul Everett Meehl. Vol. 2: Personality and psychopathology (pp. 89-113). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Wiggins, J. S. (Ed., 1996). The five-factor model of personality: Theoretical perspectives. New York: Guilford.

Wilson, M. (2005). Constructing measures: An item response modeling approach. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.